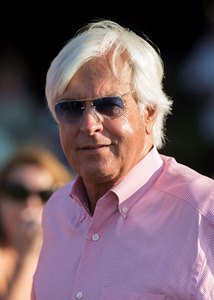

Arkansas Racing Commission Considers Baffert's Appeal

In an appeal of an Oaklawn Park stewards' decision that saw a pair of high-profile horses conditioned by Bob Baffert disqualified from 2020 victories, attorneys for the trainer and one of the affected owners argued April 19 that chain of custody violations at the lab level should have resulted in the samples being tossed rather than being used as a key piece of evidence in the stewards' ruling.

Counsel for the commission, Byron Freeland, argued that those chain of custody issues did not ultimately affect the samples or the findings. He told commission members that if they had any concerns about the validity of the initial post-race samples, a split sample that found the same positive for lidocaine should alleviate those concerns.

Baffert is appealing a stewards' decision that saw the disqualification of two horses conditioned by the Hall of Fame trainer from May 2, 2020 victories at Oaklawn. Charlatan was disqualified from a victory in a division of the Arkansas Derby (G1) and Michael Lund Petersen's eventual champion female sprinter Gamine from an allowance-level win. Petersen is appealing the disqualification of Gamine.

In a decision released July 14, 2020, following a July 13, 2020, stewards' hearing, the stewards also suspended Baffert for 15 days.

Monday's hearing, conducted in a high-ceilinged room at the hotel at Oaklawn Park Racing Casino and Resort, concluded at 5:50 p.m. CT, nearly 10 hours after it started. And the meeting was extended to a second day, as it will resume Tuesday morning.

"Chain of custody" refers to the protocols and rules put in place by regulatory bodies and labs to ensure proper collection, transport, and, eventually, identification of collected samples.

W. Craig Robertson III, an attorney for Baffert, raised a number of chain of custody issues, noting that one of the two labs involved in handling the primary sample at one point identified Charlatan as a gelding when, in fact, he is a colt. Robertson also said that same lab, Truesdail Laboratories, had received two coolers with the samples but when it shipped them to a subcontractor lab, Industrial Laboratories in Wheat Ridge, Colo., those samples were shipped out in three coolers—indicating the initial coolers were opened.

Freeland said the number of coolers was unimportant because the samples themselves were not disturbed from their collection tubes. Petra Hartmann, director of the drug testing services laboratory at Industrial, said Truesdail would register the samples but did not tamper with the samples in the tubes. Also, she later responded that opening the coolers alone would not present a significant risk of contamination.

The reason two labs are involved is because the Arkansas Racing Commission had contracted with Truesdail to handle its testing for the 2020 meet but soon after that agreement, the Irvine, Calif.-based lab lost its needed accreditation from the Racing Medication and Testing Consortium. With Truesdail unable to continue testing post-race samples from racing at Oaklawn, Truesdail reached an agreement with Industrial Laboratories to conduct the Oaklawn tests after March 17, 2020, through the end of the meet.

Oddly, according to testimony from multiple sources Monday, samples continued to first be sent to Truesdail before being forwarded to Industrial, which is accredited by the RMTC. Then Truesdail compiled data packet reports based on Industrial's findings.

The loss of RMTC accreditation at Truesdail and the subcontract with Industrial that followed certainly created issues of concern for the regulator. In testimony Monday, Truesdail's Julie Hagihara conceded that adding an extra step in the process doesn't benefit chain of custody security.

Robertson also argued that such a subcontract was not allowed. He said the original contract with the racing commission doesn't allow such an arrangement and such an approach is illegal under state law. Using an extended line of questioning of Truesdail technical services manager Anthony Fontana, Baffert attorney Steven Quattlebaum attempted to point out failures in the subcontract agreement that made it illegal under Arkansas law.

Freeland countered that the original contract allowed for updates, including the addition of a subcontract. He argued that Arkansas law has exceptions that allow such a subcontract arrangement.

In terms of the chain of custody issues, Freeland acknowledged some of these problems but argued that they did not rise to such a level of concern as to toss the sample. He said that Truesdail followed the protocol in place when it observed that the collected sample had not been disturbed and then forwarded it to the sub-contracting lab. He argued that Charlatan was correctly listed as a colt in the initial collection in Arkansas.

Hagihara said the incorrect listing of the horse as a gelding was a clerical error that occurred at Truesdail when information was input at the lab. She said it would not have affected the actual identity of the sample. Hartmann acknowledged that Industrial tested the sample with the understanding it came from a gelding but a number of experts said that when testing for lidocaine, the sex of the horse is not significant.

Summing up some of that testimony, Freeland said even if the error in listing Charlatan as a gelding created any confusion, the sex of the horse is not an important issue in testing for a painkiller like lidocaine. He said whether the horse was a colt or gelding would be an issue when testing for an anabolic steroid where there are higher thresholds for full males as compared with geldings because of the differences in naturally occurring testosterone.

Robertson extended that reasoning a bit though when he wondered, and asked a number of witnesses, why if Industrial thought the horse was a gelding, it didn't find an increased level of testosterone. He used this inconsistency to argue that it was possible evidence that the test actually may have been conducted on a post-race sample from a gelding—not Charlatan.

In response to a follow-up question, Hartmann said the findings on testosterone actually are high for a gelding and consistent with an intact male. She said a lab analyst failed to note this finding.

Freeland suggested that even if racing commission members had concerns about the primary sample, they could use the split sample that was sent to University of California-Davis. That lab also found in the split sample lidocaine at a level above the allowed threshold of 20 picograms.

Robertson disagreed with that assertion in law and in practice. In a cross examination of Arkansas state steward Bernie Hettel, Robertson referenced a previous finding in which the stewards had dropped a case over concerns about chain of custody issues involving the primary sample. Hettel acknowledged that in that case, they did not then use the second sample as evidence but rather dropped the case once it was determined that the primary sample had chain of custody issues. Hettel said he had never been involved in a case where there were concerns about the primary sample and stewards used the split sample to move forward.

An attorney for Petersen raised the chain of custody issue as well but also argued that the post-race positive for lidocaine was caused by a pain patch worn by Baffert's assistant trainer, Jimmy Barnes. He said knowing that mitigating circumstance, and considering that the lidocaine was at a level that wouldn't have affected performance, the stewards should not have disqualified the horse from the victory. He suggested in 2017 Arkansas stewards made a similar type of decision after they determined that a positive was caused by environmental contamination.

Robertson also brought up a number of other arguments: suggesting the stewards' decision was affected by the high-profile trainer and high-profile horses and races involved; that an improper leaking of the failed drug tests to the media before the split sample was received and before a stewards' hearing was scheduled adversely affected the stewards' ability to make a neutral decision; and that the current standards put in place by Arkansas under the guidance of the Association of Racing Commissioners International and Racing and Medication Testing Consortium are not scientifically based and their thresholds should be made on levels of a medication that could affect performance.

"This case should have been dismissed a long time ago," Robertson said.

Freeland repeatedly noted that Arkansas rules frequently are not in lock-step with RMTC and ARCI standards.

In testimony, it was established that other horses during the meet also showed some level of lidocaine in post-race tests, although those levels were below the threshold. Freeland said that the samples for Charlatan and Gamine came back "well in excess" of the 20-picorgram threshold with Gamine at 185 picograms and Charlatan at 46 picograms.