Allen Jerkens Left Indelible Legacy

The legacy of Allen Jerkens will live on in plenty of official documents.

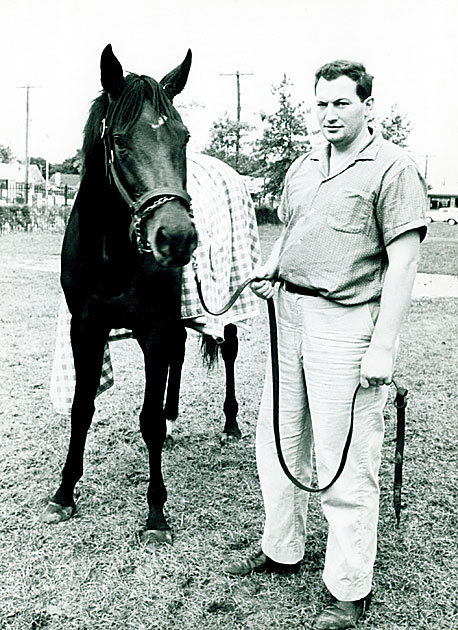

He's in charts and programs, racing manuals and the Hall of Fame, profiles and race recaps, and record books and photographs. When you train horses for more than 60 years, you leave a pretty long paper trail.

But it's not on paper—or its digital equivalent—where memories of Jerkens will endure most heartily. It's not on plaques or in photo albums, not on websites or lists of stats that his gifts to Thoroughbred racing will live on.

It's in the people he met and employed, whom he mentored and embraced. That's where, long after his physical presence is gone, we will still find the spirit of Allen Jerkens—in them and in the way they treat their horses because of his influence.

"Anybody that worked for him or was around him for any period of time was very much impacted by him," said trainer Tom Bush, who worked for Jerkens in the 1970s. "He was a great teacher and a great mentor. He was tough to please, but he made you feel good when you did right by the horses."

Bush remembered, in particular, the preparation to get a horse to a race.

"Allen called it the 'full-court press,'" he recalled. "You worked extra hard, you made sure they stayed in ice long enough, and that you took them out to graze and walk in the afternoon for a little extra time. And he was right there doing it with you."

Like so many other people around the track with Jerkens, Bush has special memories of the afternoons, not only of the legendary football games, but of what came after.

"The fondest memory I have of the Chief is at the stable in the evening," Bush said. "We'd play football and then we'd go through the horses to see who was feeling good, who cleaned up. I'd push the feed cart for him, a couple of guys would be picking out stalls, and we'd give them a little extra grain, some heavy clover or alfalfa. That was always a great time to be with him."

Retired jockey Richard Migliore never worked for Jerkens, but he was a volunteer member of that afternoon crew. After finishing up a day riding at Aqueduct Racetrack, Migliore would stop at Jerkens' Belmont Park barn, in awe of the man who was there for every feeding, who came in the afternoon and then again after dinner, individually selecting feed for each horse, tailoring it to the horse's needs. Like Bush, he came to push that feed cart, and to listen.

As a young rider who had recently lost his bug, struggling to get mounts, Migliore prevailed—as so many did—on the Chief for a job.

"We were at Hialeah," Migliore reminisced. "I asked for a shot, and I see on the overnight that he's named me on a horse. She's a speedy filly, going long for the first time.

"I take my time in the post parade—just walk her, talking to her. The gate springs and she blasts out, but in a few strides, I got her to relax. She ended up fading—she just couldn't go long—but I walk back and I'm feeling pretty good. Until I see the Chief.'"

"'She has one weapon!' he yelled at me," Migliore said. "'Horses have been running away from their enemies for thousands of years, and I get a jock that want to change evolution!'"

His temper was as legendary as his kindness. No feed bucket was safe after a tough beat or a bad ride, but his anger was as short-lived and his generosity was enduring. No matter how mad he got at you, he was pretty sure to both forget and forgive by the next time he saw you.

In the middle part of the last decade, Andrew Lakeman, a veteran of European tracks and the barn of Michael Dickinson, was working for a small trainer on the New York circuit.

"I'd always admired Mr. Jerkens, and one morning when I was walking past his barn, I stopped to talk to him, and I asked if he'd give me a job," Lakeman said. "He said that he already had too many people and that he didn't have any jobs available.

"That night, the trainer I worked for called me and told me that he had called her, and that he wanted me to come by his barn the next morning."

Before long, Lakeman was working some of Jerkens' biggest horses—Political Force, Miss Shop, and Swap Fliparoo. He was riding them in the afternoon, breaking the maidens of the horses who would go on to be stakes winners.

"When he gave the job," Lakeman said, "he told me that he could hire me to gallop, but that he couldn't ride me in any races. I said, 'No problem.'

"Two weeks later, I look at the overnight and he put me on a horse. He believed that, because we got on the horses every day and knew them, that was a big advantage for him."

Lakeman was only one of many struggling riders who Jerkens would put on a winner to get them going.

"He just helped such a tremendous number of people," Lakeman said. "I struggled with alcohol and substance abuse, and he took me under his wing. I owe him so much for that."

Seriously injured in a riding accident in May 2007 and paralyzed from the chest down, Lakeman is now a trainer and credits Jerkens with much of what he learned about horsemanship. When one of his horses, El Deal, went two-for-two last month, Lakeman's phone started ringing. Friends from Florida were calling to tell him how happy the Chief was.

"They said he was telling everybody on the track that I won," he said.

"He means so much to me," Lakeman went on. "He kept me going strong and he helped me believe in myself, not only as a rider, but as a trainer. He'll always be my hero and I'll keep him in my heart. What a great, great friend."

It is of friendship, too, that Jerkens' long-time owner Joseph Shields talks, when asked what he'll miss most about the man who trained his horses for a quarter of a century.

"I had a lot of admiration for him, for many reasons other than racing, particularly his kindness to other people," Shields said. "When you're around that barn, you see he just really has a heart, and that's a big thing in a competitive business."

Then he added, obviously having been around after one of those bad beats, "He had a competitive spirit, too, to say the least."

Jerkens got his last winner, albeit while hospitalized, with Shields' homebred Easement March 6 at Gulfstream Park. The 5-year-old was a maiden, a veteran of 16 starts who had finished first or second eight times. Jerkens may not even have been aware of the win, but Shields saw it as a direct result of the Chief's horsemanship.

"Thank goodness!" Shields said of the victory. "He'd been working on that one for a while. These are not fancy horses, but he wouldn't give up. He'd always say to (his son) Jimmy—to anybody—'Just stay with your horses.' I didn't think he'd take my horses, but he did and he ran with it."

The friend to many was also, initially, rather remarkably shy—though he'd regale visitors with stories of visiting Miami Beach hotspots during Hialeah's heyday—he usually needed a good question or two to get him going. At a Backstretch Employees Service Team event honoring him in 2008, at which speaker after speaker told admiring stories about him, his acceptance speech was exactly 15 words long.

But at the Parting Glass pub in Saratoga during the summer of 2013, with the right interlocutor, the Chief spoke for a couple of hours, to a rapt, packed house that knew exactly how lucky they were to hear him.

His host that night was New York Racing Association analyst Andy Serling, the event his weekly radio show during the Saratoga meeting.

"It was a great example of the kind of person he was," Serling said. "He wasn't exactly a young guy, and he probably gets up at 3 a.m., and yet he comes down to a crowded bar at 9:30 at night to go on the air in front of hundreds of people. It's got to be tough for anybody and he comes down there, and he's great. The respect paid to him was something I've never seen. He got a standing ovation.

"Once you start getting him going and you bring up some race or some horse, he just gets a smile on his face, and he's just as excited as any of us are. You can see when you talk to him why he became the person that he was, why he gave his life to this game, and why he continued to do it, because it clearly brought him tremendous joy and he gave that out to everybody, at any time."

Shields echoed Serling's feelings.

"When you have homebreds the way I do," he said, "they performed way beyond what I would have expected, and of course I'll miss that, but I'll miss him as a person more than that. We had a lot of laughs, and he's a great storyteller, and he's a historian. He knows what goes on in the business. And he loved it and the people in it."

"He was a good man," Shields added. "Good to the animals and good to the people."