Red Sailed into the Sunset

Trendsetters have rediscovered the 1980s, for better or for worse. It must be true if the New York Times, arbiter of all things important and trivial, ran a front-page report on the decade April 21 with the sub-headline, “…a decade often remembered fondly but with a shudder, finally gets some love.” As if to underscore this discovery, a few hours after hitting the newsstands, ’80s musical and cultural icon Prince died.

A decade that was a bit schizophrenic in trying to hold onto the past and break through to the future at the same time, the ’80s broke bounds with the past virtually across the board. If you want a sociological and cultural review, read the Times article—it is likely to curl (or, straighten) your hair.

This is salient because of the discussion my colleague Frank Mitchell and I were having on the sale grounds at the Ocala Breeders’ Sales Co.’s spring sale. I had mentioned I was looking for a topic for this column, thinking on a theme of “why Thoroughbred families, or sire-lines, die.”

At the risk of self-promotion, that conversation with Mitchell and the emergence of the 1980s retrospection prompted me to ask the rhetorical question, “Wonder what has happened with the Red Sunset crowd.”

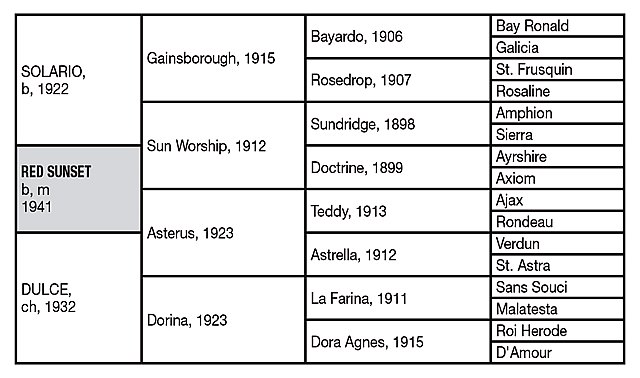

Red Sunset, a 1941 foal by classic winner Solario out of Dulce, by French stayer Asterus, had the distinction of coming from a classic-oriented family in Great Britain and France. She continued that orientation as her daughter Crepuscule (by Mieuxce) produced the champion and sire Crepello as well as classic winner Honeylight, whose branch gave us four group winners. Red Sunset’s daughter Mieux Rouge (by Mieuxce) produced Grand National Steeplechase winner Pattered as well as Better Honey, who was a leading sire in New Zealand. However, the family seemed to go quiet at the end of the 1980s.

Red Sunset much earlier had caught our attention because of her son Rasper II, a son of Gold Cup-winning stayer Owen Tudor, who was imported into this country by Sally Bierer’s Woodside Stud of New Jersey. Rasper II was atypical of his family in that he had speed and although he never won or placed in a stakes, he won 11 of his 33 starts for Woodside and was retired to stud in New Jersey. From only 57 foals (54 starters) he sired six stakes winners, including two remarkable stallions: Rambunctious and Rock Talk.

These two became popular in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast by siring early-maturing, good-feeling, speedy offspring that won tons of races. Rambunctious sired 14 stakes winners including the popular and successful Maryland sire Rollicking. Rambunctious’ best runner was three-time grade I winner Jameela who produced the excellent runner and sire Gulch (by Mr. Prospector).

Rock Talk, while at stud in Maryland, got 23 stakes winners, including multiple grade I winner Heartlight No. One, champion 3-year-old filly of 1983. He also sired Talc, a multiple stakes winner who went on to become a leading sire in New York.

Rasper II was an anomaly: He had 11 multiple crosses of mostly classic, solid, and professional sires in his five-cross pedigree and his Dosage Profile (6-4-12-10-14) reflected that. Yet he and his sons and grandsons delivered speed for the most part—tactical, stalking, explosive speed—and helped shape the racing population of the Mid-Atlantic for three decades.

And after the 1980s...they virtually disappeared.

Back to Red Sunset whose daughter Red Infiltration (by Irani) was responsible for Lancashire Oaks winner Red Chorus (by Chanteur II); and her branch also produced a number of other black-type winners. However, this is the only other branch that came to the U.S., so to speak, and this correspondent knows it well.

Red Infiltration’s daughter Red Harmony (by Hard Ridden) was imported to this country where her winning daughter Harmoniously (by Belmont Stakes winner Quadrangle) was bred to Nehoc’s Bullet, a son of Sword Dancer. That mating produced Behind the Groove, whom this correspondent obtained as a broodmare prospect in 1983.

In one of the most fortuitous matings one could think of, she was sent to Weth Nan, a French group-winning son of Drone at stud in New York and the result was a colt whom The Jockey Club allowed to be named Omar Khayyam. He became a state-bred champion sprinter, his dam established a viable branch of very modest winners by various sires, and she is now resting in peace at Equine Advocates in Valatie, N.Y. We obtained Behind the Groove only because she traced to Red Sunset, whose family, paraphrased by the lyrics of Bing Crosby’s song, has not quite sailed “way out on the sea,” but rather simply disappeared.