Nack BackTrack: Reliving That First Kentucky Derby

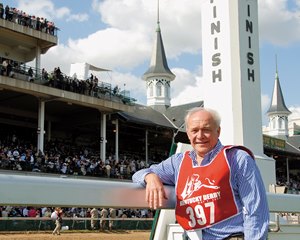

At 6:15 on May 3, 2008, as I was standing by the finish line pole on the turf course at Churchill Downs, leaning hard into gusting 25-mph winds and even harder into winds of history, you could hear the track announcer's distant voice echoing that the horses were "all in." And then, suddenly, there came this comber of sound rolling across the Downs as 157,770 soul mates—the second largest crowd ever to witness a Kentucky Derby—cheered the horses leaping from the gate.

For a moment, as the field of 20 came hurtling past me, it was like an old dream come alive again, a familiar scene in Technicolor replay, with the whole of those sights and sounds coalescing suddenly in a remembrance of things past, a vision clear and true.

On that very day 50 years before, May 3, 1958—fully 18,263 afternoons ago, to be exact, almost to the very hour—I was standing in that same spot at Churchill Downs and watching a similar stampede come rushing by no more than 20 feet away. Late in April 1958, when I was serving time as a 17-year-old junior at Niles East High School in a suburb of north Chicago, I received a telephone call from my mother's brother, a collegial uncle named Edward Feeney, who had been for years a leading sports photographer at the Chicago Tribune.

By then, Uncle Ed had heard me recite from memory all the Kentucky Derby winners from Aristides in 1875 through Iron Liege in 1957; knew that I carried in my thin wallet a photograph of Swaps, the 1955 Derby winner and the only boyhood hero I ever really had; and understood I was a regular habitué of all the greater gambling halls around Chicago, from Washington Park in in the south to Arlington Park in the north. Ed himself was a carrier of the racetrack gene, a gambler who loved to play, and I got the sense, when he called that day, that he wanted to observe my own form of the neurosis up close—in that celebrated gambling emporium known as Churchill Downs.

"I'm going to Kentucky to shoot the Derby in a couple of weeks," Ed said. "Would you like to go?"

Truth be told, tell me how else could a 17-year-old kid, with the picture of a racehorse in his wallet, answer that?

Next thing I recall, after a long ride south by train to the River City, I was sitting in a room at the old Brown Hotel on Thursday night, May 1, and watching Ed's roommate, David Condon—then the lead sports columnist at the Tribune—write his Friday column for the paper. Reading that piece the next day, with his lead describing a set of Calumet horses walking to the track for their morning calisthenics, "moving as majestically as cavalry" to the Downs, I was struck by the quite romantic nothing that writing about this sport—about the colorful world and the nobility of these animals—might be a wonderfully pleasant way to make a living.

Early Friday morning, the day before the Derby, I found myself in the very epicenter of that world, trailing Ed and David as they made their rounds on "The Dawn Patrol," that party of writers who meandered before breakfast from one barn of Derby horses to the next. Even today, all these years later, I can still see Ed shooting pictures of Gone Fishin' and his trainer, Charles Whittingham, as Charlie led the colt through the gap to the racetrack for a final gallop. Can still see the writers gathered around penny-bright Silky Sullivan, already a stretch-running immortal, as he was given a sudsy, warm-water bath. Can still see that very large man, under his white fedora, as he sat on a raw-boned pony outside Calumet's barn, not far from where Gen. Duke, the 1957 Derby favorite until he went wrong, was nibbling on a patch of sunlit grass by the Longfield Avenue fence.

The man beneath the fedora was Ben A. Jones, known by then as the greatest trainer of the running horse in the 20th century, the head man at the farm that had produced the immortal Citation. Having just spent the morning with all those reporters on The Dawn Patrol, I yielded to the temptation to be one of them, and so I approached the old man doing my very first and finest impersonation of a turf writer.

"Who's the greatest Calumet horse ever?" I asked,

"Armed," Ben said, referring to the mighty Calumet gelding of the 1940s.

"Armed?" I gasped in disbelief. "What about Citation?"

"Armed could do anything," the old man growled, "and carry weight doin' it."

At 3:45 p.m. Saturday afternoon, toting a bag of Ed's cameras and film, I toed my way cautiously along wooden planks laid across the muddy track. Ed positioned one camera under the rail, shooting up at the finish, while I stood back watching the post parade and this truly remarkable scene as it unfolded before me.

At precisely 4:32, at the top of the stretch, the 14 Derby horses left the gate; just 23 1/5 seconds later, sounding like a troop of cavalry moving at attack speed, they all came racing past not 20 feet away. A whippet-quick little bay named Lincoln Road was leading into the first turn, with Calumet's favored Tim Tam, jockey Ismael "Milo" Valenzuela up, slogging along in the middle of the pack. From behind them, in a fleeting gust of glory, came Silky Sullivan, by then already so far behind that he came galloping past us all alone. In fact, Bill Shoemaker, who was riding Silky that day, looked like the coolest ambulance driver ever to chase a field into the clubhouse turn. Ninety seconds later, with the crowd roaring even louder now, in a pitched and desperate struggle the final 100 yards, Tim Tam surged past Lincoln Road to win it by a half-length. And moments later, to gusting cheers, Ben Jones and his son Jimmy were leading Tim Tam to the charmed circle while Valenzuela, wiping the mud from his face, beamed at the crowds.

This was the single most colossal experience of my youth, to be sure, the seminal event in defining my journalistic life. Some four years later, with a nod to David Condon, I entered journalism school at the University of Illinois, and nine years after that I was plodding along as a political writer at Newsday newspaper, on Long Island, when my life turned on a miracle of perfect timing. Once again that long roll-call of Derby winners, memorized so many years ago, surely saved me from a fate even worse than covering the White House. At the annual bourbon-laced, egg-nog Christmas party at Newsday, at the urging of friends, I mounted a table in the middle of the city room and recited all those Derby winners, from Aristides through Canonero II; as I climbed down to cheers.

The paper's editor David Laventhol came by and whispered, "Why do you know that?" I told him the whole story, about hanging out at racetracks since I was a kid, about the photo in my wallet, which I recall he asked to see, and about my trip to Churchill in '58. Five minutes later, David decreed that I would be Newsday's new Thoroughbred racing writer, and I've been impersonating one ever since.

So here it was, all these Derbys later—38 in all, 36 and counting since Riva Ridge won in 1972—and it seemed the ideal moment to glance back and remember: Secretariat's incomparable run into history in 1973, with a final half-mile in: 46 2/5; Seattle Slew's fullback charge through traffic to take command early in '77; Alydar's vain effort to overtake Affirmed in '78; Genuine Risk's bold rush to the lead off the final bend in '80, her green silks flying; Shoemaker's brilliant handling of Ferdinand, finding daylight coming home in '86; Alysheba's miraculous recovery from a near fall after clipping the heels of Bet Twice in '87; Carl Nafzger's call of the race for Frances Genter, nearly blind, as her Unbridled charged to victory in '90; and Barbaro's magnificent coup de grace on the last turn to win by nearly seven in '06.

From the finish pole on Saturday, the renovated Churchill rose up before us like a giant ocean liner marooned on a Kentucky moraine, with the Twin Spires rising as smokestacks, its five decks crawling with people. They stood as one from the start. The horses left the gate to a thunderous din, and as they raced past us in the sunlight, with silks flashing, dirt flying, you could see the horses running low and straining as they bucked the wind. A minute later, the sound grew louder, richer, as Big Brown swept by the game, ill-fated filly, Eight Belles, to take the lead. Big Brown came home running well within himself, his strides steady and fluid, his left eye glinting as he bounded past the wire, enjoying a much easier time of it than Tim Tam did five decades earlier.

Of course, most of them from those good ol' days are gone now—Ed and David, Ben and Jimmy, Charlie and The Shoe, and all the pretty horses. But there is at least one other witness who still survives. Milo Valenzuela is 73, battling diabetes and high blood pressure, but he's had ample cause to celebrate this spring. Years too late, he was finally elected into the Racing Hall of Fame at Saratoga—"I couldn't believe it," he said by phone May 2—and he still has Tim Tam's Derby to remember.

"It was my first time in the Derby," he said. "It was a big thrill for me."

Me, too, Mil. And thanks.